Globalization is one of the great issues facing universities today, particularly in humanities departments. It means different things to different people, but most agree that globalization pluralizes. In the words of Jonathan Arac, globalization “opens up every local, national or regional culture to others and thereby produces ‘many worlds.’” However, this rapid pluralization is occurring in the age of English, when a single language has achieved a dominance hitherto unknown in world history. As a result, the many worlds opened up by globalization are increasingly likely to be known through that single language alone.

Globalization is one of the great issues facing universities today, particularly in humanities departments. It means different things to different people, but most agree that globalization pluralizes. In the words of Jonathan Arac, globalization “opens up every local, national or regional culture to others and thereby produces ‘many worlds.’” However, this rapid pluralization is occurring in the age of English, when a single language has achieved a dominance hitherto unknown in world history. As a result, the many worlds opened up by globalization are increasingly likely to be known through that single language alone.

The combination of globalization and “Globlish” paradoxically tends to flatten foreign cultures even as it enhances their accessibility. Minae Mizumura’s recent book, The Fall of Language in the Age of English (skillfully translated from the Japanese by Mari Yoshihara and Juliet Winters Carpenter) reveals the various consequences of that flattening from the perspective of a prominent writer working in a non-European language. For those living in the Anglosphere, no barrier seems to stand between their world and the many other worlds that now appear at the push of a button. But for those outside that world, particularly in non-European countries, the literary and linguistic consequences of globalization in the age of English can often be severe.

Mizumura’s book met with fierce hostility in Japan when it first came out in 2008. The original Japanese title means literally “when the Japanese language falls: in the age of English.” Largely because of the provocative title, which suggests the imminent demise of Japanese, it caused a furor and became an Internet sensation in which legions of bloggers gave their opinions, sometimes without even bothering to read the book. Mizumura was attacked from both ends of the political spectrum. On the right she was criticized as anti-Japanese and anti-nationalist for implying that the Japanese language had weakened in the face of English. In the book, she advocated returning to the great Japanese novels of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which she considered the peak of modern Japanese literature and a means to revitalizing literary Japanese and Japanese language education as a whole. This stance caused her to be attacked on the left as reactionary and elitist, as a writer who harked back to the dark pre–World War II days and the country’s imperialist past.

The fierce argument across digital media helped make a national best seller (a rare phenomenon for such an academic book), with over 65, 000 copies sold to date, and stirred a national debate about the weaknesses of both Japanese and English education in Japan. Despite the book’s title, Mizumura does not actually believe that the Japanese language is about to collapse; instead she is concerned about the diminishing quality of literary Japanese and the fate of contemporary Japanese literature in an era of English.

Source: www.publicbooks.org

You might also like:

Related posts:

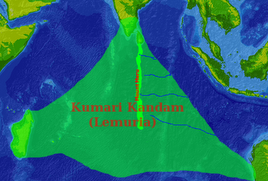

Devaneya Pavanar (ஞா. தேவநேயப் பாவாணர்; Ñānamuttaṉ Tēvanēya Pāvāṇar; also known as G. Devaneyan, Ñanamuttan Tevaneyan; lived 1902–1981), was a prominent Indian Tamil author who wrote over 35 books. Additionally, he was a staunch proponent of the "Pure Tamil...

Devaneya Pavanar (ஞா. தேவநேயப் பாவாணர்; Ñānamuttaṉ Tēvanēya Pāvāṇar; also known as G. Devaneyan, Ñanamuttan Tevaneyan; lived 1902–1981), was a prominent Indian Tamil author who wrote over 35 books. Additionally, he was a staunch proponent of the "Pure Tamil...